Nigeria, Abuja

CNN

–

The reductions to the US-funded malaria program are adding to many of the issues facing Congolese mother Mwemai Defeza.

“I have a sick child. He has been suffering from malaria for a week and several days,” Feaza, 36, told CNN about his one-year-old son, whom he suspects is caused by a mosquito-borne illness.

She also experienced symptoms of the illness, she said. “It feels cold. I feel a pain in my mouth.” The single mother said she had no work, had far less malaria treatment for her and her baby, and barely could afford food.

Malaria is a preventable and curable disease, but it claims the lives of hundreds of thousands of people around the world each year. Toddlers, children under the age of 5, and pregnant women are most likely to die from malaria infection.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), this is the leading cause of death in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which is the world’s second-highest malaria burden after Nigeria. It was estimated that about 24,000 people died from illness in Central African countries in 2022. More than half of these deaths were children under the age of five.

An estimated 36% of US International Development Agency (USAID) funding for malaria programs has been cut since the Trump administration began cutting foreign aid earlier this year, according to the Center for Global Development, a DC-based think tank. However, the true level of aid reduction remains uncertain.

At DRC, the funding funded anti-malaria supplies to “many health zones” across the country “including intermittent preventive treatment for pregnant women,” according to Michelle Itab, a former spokesman for the country’s National Malaria Management Program (PNLP).

“PNLP already feels the impact of the funding cuts,” Itab told CNN. Such a prevention program may be protecting Idi Feaza and her baby son. Instead, if they get infected, they both run the risk of serious illness or death.

For a long time, the US government has been the biggest donor of global efforts to combat malaria. For decades, USAID led a program called the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), which reduced mortality rates and eliminated malaria in 30 of its most intense hit countries. The program, launched in 2005 by George W. Bush, helped reduce malaria deaths by more than 60%, saving millions of lives.

CNN spoke with several people who had previously worked on the initiative but were recently fired during Trump’s USAID demolition. Most PMI staff were either let go or stopped working due to the order to stop work. The Trump administration’s proposed budget called for a 47% cut in the program.

All aid workers who spoke to CNN emphasized that people will die in the short term as a result of the disruption in malaria prevention and treatment efforts.

In the long term, they said cuts in funding would destroy years of American progress in driving the prevalence and severity of the disease.

The US-backed surveillance system, once the backbone of efforts to monitor malaria and other disease outbreaks around the world, has also been cut, a former U.S. government worker told CNN that it has highlighted long-term concerns.

“One reason we don’t have malaria in the United States is to fund and track malaria around the world for global health security,” the former USAID contractor told CNN anonymously in February, fearing retaliation. She warned that locally acquired malaria cases, like Florida she experienced in 2023, could become more common than “if you’re not driving a parasite elsewhere.”

Aid workers and nonprofits argue that the malaria program and US illness surveillance will make America “safeer, stronger and more prosperous.”

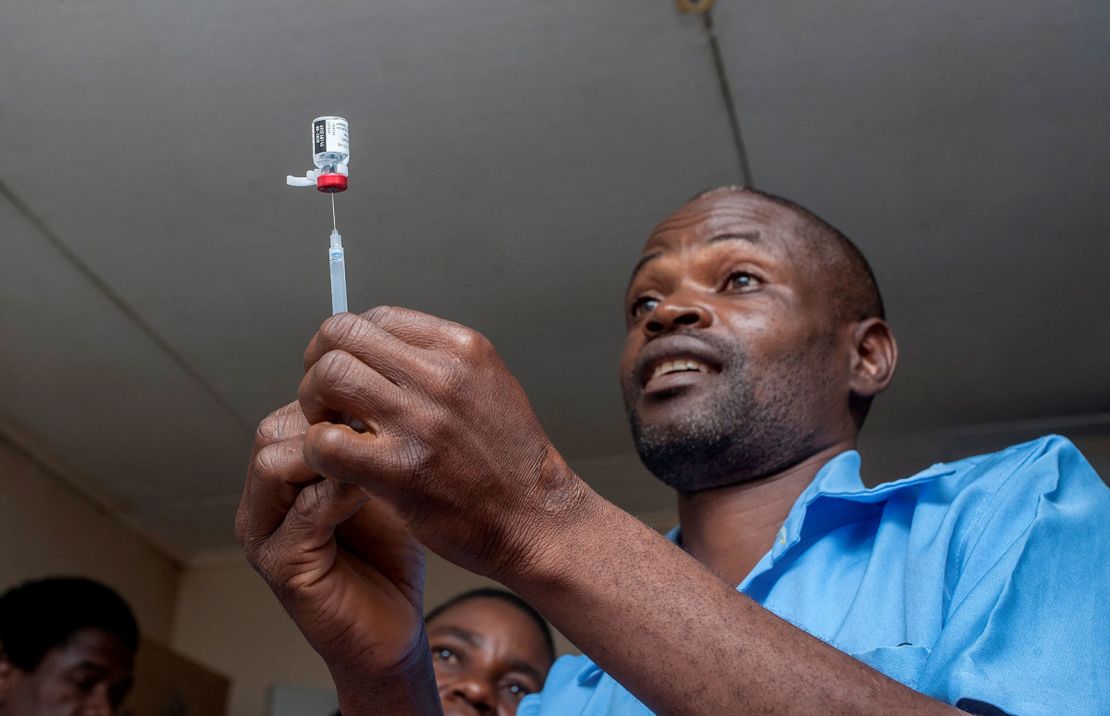

For example, USAID and the US military have long invested in malaria vaccine research, reducing the burden of global disease and protecting US soldiers overseas.

“The world’s most dangerous infectious diseases, including Ebola, Marburg and the pandemic flu, are often first, allowing malaria detection programs to stop running,” Spencer Knoll, the US policy and advocacy director for nonprofit malaria, in testimony to the U.S. House Approximately Expenditure Committee.

The nonprofit also argued that US support would prevent other countries, such as China and Iran, from making further invasions into Africa in terms of soft power.

“Everything that comes from USAID was very intentionally branded, with this logo saying “From Americans.” “They’re looking forward to seeing the company have been working on a daily basis,” said Ann Linn, former PMI contractors who lost their jobs in January. “When all of a sudden, when everything stops, it just tears trust not only from our governments to the rest of the government, but within the country’s health system.”

According to the WHO, between 2010 and 2023, the US contributed more than a third of the world’s malaria fundraising.

As of last year, the US was also the biggest contributor to a global fund working to combat AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. It is unclear what future levels of US funding for independent public-private programs will be.

The Trump administration’s fund cuts could “have decades of progress through years of investment from the United States and other global partners,” he warned in a statement earlier this year. “Funding for some US-backed malaria programs has recovered, but the disruption leaves a significant gap.”

The US State Department did not answer questions about the orders from CNN for a halt work and where PMI’s budget cuts are particularly felt.

Former aid workers highlighted concerns about a lack of investment to tackle several global threats related to malaria, including drug-resistant, pesticide-resistant mosquitoes and new invasive mosquitoes migrating to urban areas with a larger population.

“All of this timing doesn’t get worse. Malaria is seasonal, so interruptions during seasonal times will bring us back significantly,” said Nathaniel Mueller, a senior innovation advisor at PMI, whose jobs were cut back in January. He warned that there will be a rise in case baseline this year, allowing for further spread of future illnesses due to low funding for measures such as bednet and preventive care.

“You missed that window and you can’t go back to that first baseline…it’s going to rise,” Mueller said. “We risk losing years of investment and seeing a huge increase in caseloads.”

That bad timing is particularly pronounced in Malawi, where recent floods and cyclones have promoted malaria infections, the country’s national malaria management manager Lumbani Munthali told CNN. He added that “USAID funded cuts for malaria intervention put the country in a “difficult situation” as “it’s not easy to close the gaps created.”

Over 2,000 people died from malaria last year in Malawi. Approximately 9 million people have been infected.

“Malawi has made great strides in reducing malaria deaths due to technical and financial support from the US government,” Munsari said. That funding was spent raising millions of malaria test kits each year, providing pregnant women and nursing mothers with insecticide-treated bednets and anti-malarial medications.

“We’re trying to close those gaps, but we may not close them completely,” Munsari said as Malawi adapts to the sudden drop-off of US foreign aid. According to an analysis by the Global Development Centre, approximately 64% of Malawi’s USAID funding has been reduced across all programs.

In 2023, the most recent year when PMI numbers are available, Malawi received $24 million in the fight against malaria. Munsari said it is not yet clear how much they will be lost this year.

Aid workers also warned that reductions in US foreign aid to other regions, such as the malnutrition program, would have overlapping effects in Africa.

“Very malnourished children become more vulnerable to other diseases,” such as measles, cholera and malaria, according to Nicholas Moolie, emergency coordinator for doctors without borders or emergency coordinator at Medesin Sun Frontier (MSF), who works in northwest Nigeria. He said the funding gap for malnutrition programs that were already in existence in 2024 has deepened significantly this year.

Malaria infections can lead to malnutrition and fuel what MSF calls “vicious cycle.”

Nigeria’s Health Minister Muhammad Ali Pate told CNN that it has mobilized domestic funds in the health sector, including $200 million recently approved by Congress to mitigate the impact of the government losing its USAID funds.

“When US government changes occur and policies are made, we can reset it and consider it another opportunity to increase domestic funding and meet our population health responsibilities,” he said. “After all, the responsibility for the health of Nigerians lies with the Nigerian government. This is by no means a major responsibility of the US government.”

Although MSF does not rely on US government funding, the organization said additional patients are responsible following the US cuts to other humanitarian actors in the region. “We don’t have the ability to handle all of them,” Mully said.

Aid organizations prepare for the annual peak of malnutrition when autumn harvests have not yet arrived and the rainy season is increasing the number of malaria cases – by stockpiling ready-to-use medical food bags. However, in this year’s lean season, Moolie said there was “uncertainty” about their availability.

“We can expect a very serious situation,” Moolie said, stressing that the child will die as a result. “We haven’t seen anything like this when it comes to global aid disruptions. It’s very difficult.”