Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory Science Newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific advances and more.

CNN

–

The story of two of the strangest animals on the planet has just won a small stranger thanks to clues revealed by lonely fossil specimens that scientists say are now injured for a long time. This new study can overturn what is known about the evolution of the most primitive mammals living today.

The platymonds and echidnas found in Australia and New Guinea are known as monodoci and are unique because they are the only mammals that lay eggs.

Amphibious platy trees have duck-like bills, webbed legs and beaver-esque tails. Small creatures spend a lot of time hunting food underwater. Echidna, aptly known as a spiny alititer, is completely on land, covered in pointy quills, and heads backwards, kicking dirt as the animals dig holes into the ground. Both animals do not have teeth, so they both produce milk, but because they lack nipples they secrete it through the skin for babies (often called puggles).

“There’s a lot of weirdness about going around these little things,” said Dr. Guillermo W. Rougier, professor in the School of Anatomy and Neurobiology at the University of Louisville, at the University of Kentucky, who studies early mammal evolution.

“They are one of the definitive groups of mammals,” Luzier said. “The typical mammals from the dinosaur era shared more biology with the monotome than perhaps horses, dogs, cats, or ourselves.” So he said he would provide a window into the origins of mammals on Earth.

A new study, published on Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, opens its window a little more. The study, led by paleontologist Suzanne Hand, professor emeritus at the University of New South Wales in Australia’s School of Biology, Earth and Environmental Sciences, reveals the internal structure of only known fossil specimens of the Monotome ancestor Kryolicce Kadberic, who lived 100 million years ago.

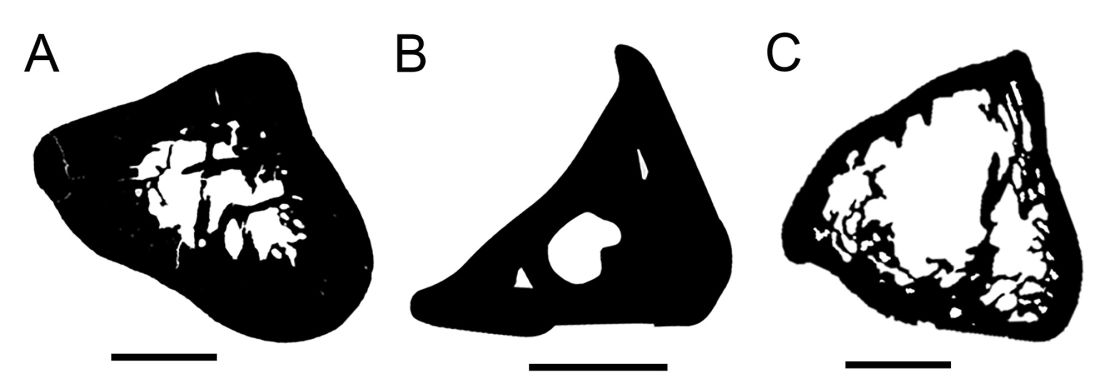

Fossils, humerus, or upper arm bones were discovered in 1993 in a dinosaur cove in southeastern Australia. From the outside, the specimen looked more like the bones of land-based echidna, rather than water-loving karauma. But as researchers looked inside, they saw something different.

“Using an advanced 3D imaging approach, we were able to illuminate previously unseen features of this ancient bone, which revealed very unexpected stories,” said Dr. Laura Wilson, a senior lecturer at the School of Biology, Earth and Environmental Sciences, who co-authored the study.

The team discovered internally that the fossils have semi-quantitative Katani properties. It is a thick bone wall and a smaller central cavity. Together, these properties make the bones heavier. This is useful in aquatic animals to reduce buoyancy, making it easier for creatures to dive underwater and forage food. In contrast, Echidnas, who live only on land, have much thinner and lighter bones.

This finding supports the popular but unproven hypothesis that Cliolic is a common ancestor of both Karitta and Echidna, and at the time of the dinosaurs, they may have lived at least partially in the water.

“Our research shows that the amphibious lifestyle of modern platy deer had its origins at least 100 million years ago,” Hand said.

The evolution of the alama stye

There are well-known examples of animals that evolve from land to water. For example, dolphins and whales are thought to evolve from land animals and share their lineage with hippos. However, there are few examples of evolution from water to land. The transition requires “a significant change to the musculoskeletal system,” Wilson said.

The transition from land to water can explain the strange rear foot of Echidna. This may have been inherited from swimming ancestors who used their hind legs as ladders, Hand said.

“I think these animals are very elegantly proof that they were adapted to six months of life very early,” said Luger, who was not involved in the study, but came into contact with the author during the study.

The primitive history of these rare animals is “really important” to understand how mammals (including humans) have turned out.

“Monotrem is these living relics of a very long past. You and Karatis had their last common ancestors, probably over 180 million years ago,” he said. “There is no way to predict the biology of this last common ancestor without animals like Monotrame.”

Amanda Schpack is a New York City science and health journalist.