Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory Science Newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific advances and more.

CNN

–

On a May night in 1337, when a group of men approached a priest named John Forde, the sun was set on busy London Street. They surrounded him in front of a church near the old St. Paul’s Cathedral, stabbed him in the neck and stomach, then fled.

Witnesses identified his murderer, but only one assailant went to prison. And Ella Fitzpain, a wealthy and powerful nobleman who could have ordered a brave and shocking hit, was not brought to trial, according to historical records explaining the case.

Almost 700 years later, new details emerged about the events leading up to the brutal crime and the nobility behind it. Her criminal transaction included theft and fear tor, as well as the murder of Forde, who was also her ex-love.

According to recently discovered documents, Forde (his name appeared in the record as “John de Forde” as “John de Forde”) could have been part of a crime gang led by Fitzpayne. The group took away a nearby controlled monastery that controlled France and used England’s worsening relationship with France to force the church, researchers reported in a study published at the Criminal Law Forum on June 6.

But the whimsical priest may have betrayed Fitzpain to his religious superior. The Archbishop of Canterbury wrote in 1332 that a new report also linked to Forde’s murder. In the letter, the Archbishop condemned Fitzpain, accusing him of committing serial adultery “single, single, married, and even with a clergyman on holy orders.”

The Archbishop’s letter appointed one of the many paramers of Fitzpain. Forde was the president of a parish church in the village of the Fitzpaine family’s property in Dorset. This terrible accusation led the church to assign Fitzpain to a humiliating public penance. According to Dr Manuel Eisner, a professor at the University of Cambridge in the UK and director of the Crime Institute, she assassinated her revenge several years later and forced her to be revenge.

This 688 murder emailed Dr. Hanna Skoda, an associate professor of medieval history at St. John’s College at Oxford University in the UK, “provides us with further evidence of clergy entanglement in secular issues and the very active role of women in managing women’s relationships and relationships.”

“In this case, the event was dragged out for a very long time, demanding grenades and revenge, and emotionally active,” said Skoda, who was not involved in the research.

According to Eisner, new clues on Forde’s murders provide a window into the dynamics of medieval revenge killings and how they were in displays of power in honorable public spaces.

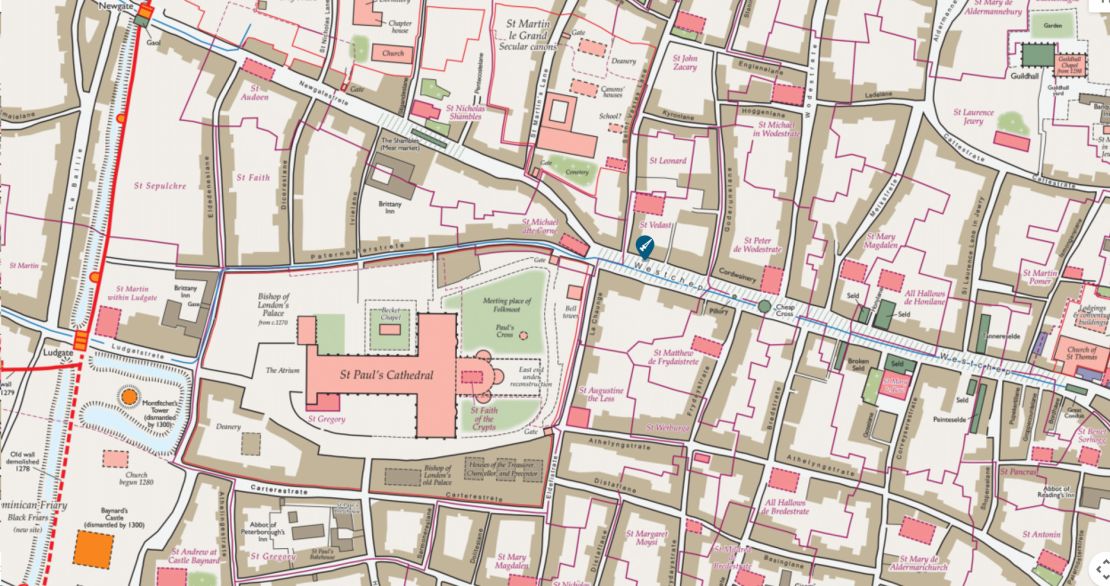

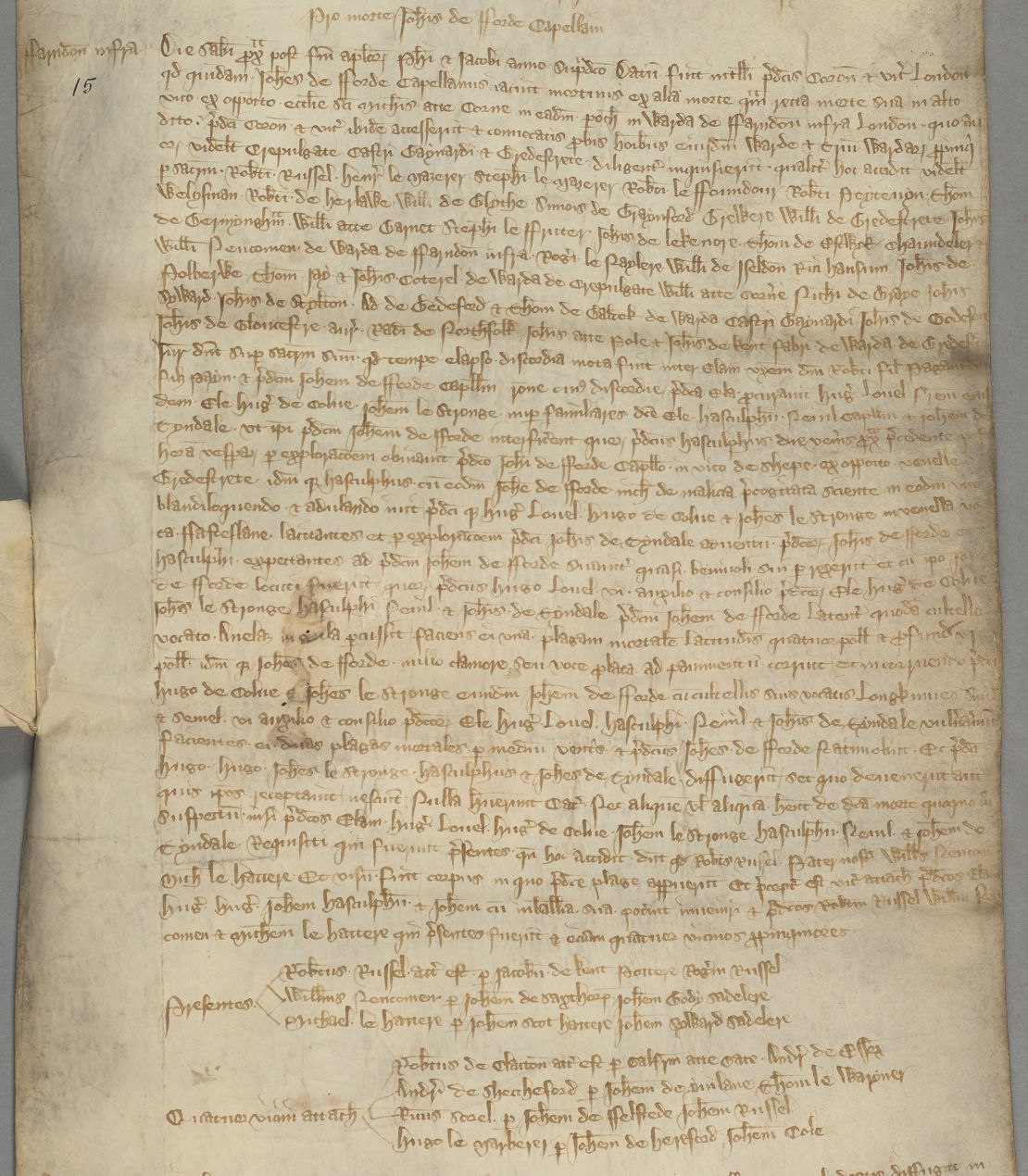

Eisner is the coctor and project leader of Medieval Murder Maps, an interactive digital resource that collects murders and other sudden or suspicious deaths in 14th century London, Oxford and York. The project, launched by Cambridge in 2018, translates reports from records written by a Latin medieval coroner who focuses on crime details and motives, based on the deliberations of local ju apprentices. The ju judge listens to the witness and examines the evidence before naming the suspect.

In the case of Forde’s murder, coroner Roll said Fitzpain and Forde had argued and persuaded four men, her brother, two servants and a pastor, to kill him. On that fateful night, his accomplice attacked as the pastor approached Forde in the street and deflected him in conversation. Fitzpain’s brother slit his throat, and the servant stabbed Forde in the belly. One of the attackers, a servant named Hugh Corne, was indicted in the case and was imprisoned in Newgate in 1342.

“I was initially fascinated by the texts on the coroner’s records,” Eisner told CNN via email, describing the event as “a dreamy scene that can be seen for hundreds of years.” This report made Eisner want to learn more.

“I would like to know what the members of the ju umpire discussed,” he said. “I wonder how and why ‘Ella’ persuades ‘Ella’ to kill the priest, and what the nature of this old argument between her and John Forde was. That’s why I started to look into this further. ”

Eisner followed the Archbishop’s letter in a 2013 paper by medieval historian and author Helen Matthews. The Archbishop’s accusations allocated severe punishments and official penance to Fitzpain, including donating large sums of money to the poor, refraining from wearing gold or precious gems, walking the length of Salisbury Cathedral towards the altar, and carrying around four pounds of wax candles. She was ordered to do this so-called walk of shame for seven years.

Although she appears to have rebelled against the Archbishop and never played repentance, the humiliation “may have caused her thirst for revenge,” the study author writes.

The second clue where Eisner was unearthed was ten years older than this letter. Investigation of 1322 of Forde and Fitzpayne by the Royal Commission following complaints filed by the French Benedictine abbey near Fitzpayne Castle. The report was translated and published in 1897, but at that time it was not yet related to the murder of Forde.

According to the indictment of 1322, Fitzpain’s crew included Folde and her husband, Sir Robert, a knight of the realm – destroyed the gates and buildings at the Priory, stole about 200 sheep and lambs, 30 pigs and cows, and returned to the castle and held them for Ransom. Eisner said she was surprised that Fitzpain, her husband and Forde were mentioned in the case of the pastor’s upset turmoil during an era of political tensions with France.

“The moment was very exciting,” he said. “As a member of a group involved in a low-level war against French monasteries, I would never have expected to see these three.”

In British history, city residents were no strangers to violence. In Oxford alone, the rate of murder in the late Middle Ages was about 60-75 deaths per 100,000 people, about 50 times higher than what is currently seen in British cities. One of the Oxford records describes “a rampage scholar with bows, swords, bucklers, slings and stones.” Another mentioned the altercation that began as a tavern discussion at a tavern, then escalated into a massive street brawl that included a blade and a combat axis.

But while England was a period of violent nature during the Middle Ages, “this doesn’t mean that people didn’t care about violence,” Skoda said. “In the legal context, political context, and in the community, more broadly, people were really worried and suffering about high levels of violence.”

The Medieval Murder Map Project “provides engaging insights not only about how people carry out violence, but also how people worried about it,” Skoda said. “They were reported, investigated, charged and they were really dependent on the law.”

Fitzpain’s intertwined web of adultery, coercion and assassination also reveals that despite social constraints, some women in late medieval London still had agency.

“Ella was not the only woman she recruited men to kill to protect her reputation,” Eisner said. “We see violent events that arise from a world where upper class members are experts in violence and can be killed as a way to maintain power.”

Mindy Weisberger is a science writer and media producer who appeared in Live Science, Scientific American and How It Works Magazine. she”The rise of zombie bugs“The Amazing Science of Parasitic Mind Control” (Hopkins Press).