Historians and activists say it’s important to protect sites like the Harriet Tubman Visitor Center, which tells many stories from the past.

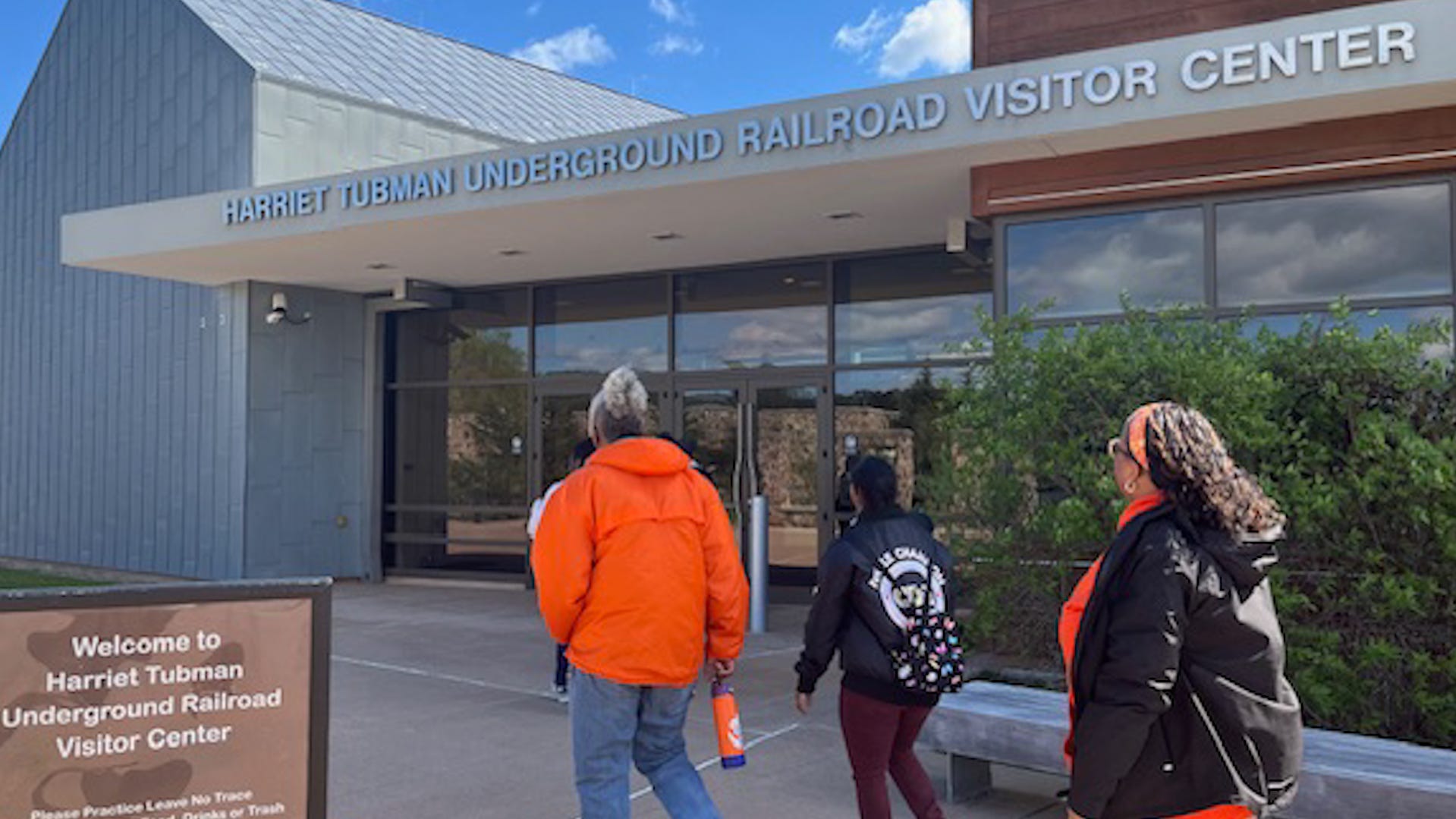

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Centre supports her legacy

The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitors Centre is one of two national historic parks that continue to live on the heritage of the abolitionist.

Church Creek, Maryland – Deanna Mitchell pointed to a bronze bust of Harriet Tubman at the entrance to the center, urging visitors to feel the scars by touching the nape of their neck.

She explained that the bust she described was heading north where Tubman led dozens of enslaved people freely.

“It was a dark time,” Mitchell said., Supervisor of Harriet Tubman Underground Railway National Historical Park, which includes the Visitor Center.

Tubman has been the subject of new public interest in recent weeks as the Trump administration temporarily removed information about abolitionists from the National Park Service website.

Tubman’s photos and quotes were restored after the fuss, but the move raised alarms amid other cases where black and Native American figures were temporarily removed from federal websites.

In President Donald Trump’s first three months, he has repeatedly targeted Day, or criticised as an unfair “wake-up” policy to promote diversity, equity and inclusion. As part of that critique, he targets “revisionists” who speak of American history, highlighting events that he describes as negative.

“For the past decade, Americans have witnessed a coordinated and broad-ranging effort to rewrite our country’s history and replace objective facts with distorted stories driven by ideology rather than truth,” Trump wrote in his March 27th enforcement order.

In recent years, the National Park Service has promoted efforts to maintain the history of underrated groups, rehabilitating and constructing the narratives of abolitionists like Tubman last year, along with Japanese that interns in World War II and forgotten Mexican farmers.

But many historians, civil rights activists and educators worry that these kinds of efforts may be reduced or even eliminated as the government reshapes how government presents the American past.

“Serious historians, scholars, or cultural experts believe that America’s issues are talking too much about the history of racial injustice, the history of slavery and lynching and separation,” said Brian Stevenson, founder of human rights group Brian Stevenson. “The problem was the opposite.”

And Meeta Anand, senior director of census and data equity at the Centre and Human Rights Leadership Council, sees federal change as an attempt to control the American narrative.

“It represents a very intentional effort to erase the contributions made by a particular community and the community,” she said.

“History has tentacles.”

On a recent Wednesday, Mitchell led visitors through an exhibition telling the story of Tubman’s life. She explained how abolitionists bravely encourage death to help families and other enslaved blacks flee along the Underground Railroad.

“She lived long based on what she had to endure,” Mitchell told them.

The centre is one of two national park service sites that tell the story of Tubman. The other was in Auburn, New York, where Tubman lived until his later death at 91.

The center, co-managed by Maryland Park Services, had 30,000 visitors last year. Many people were there before.

“The visitors actually stay where she was and learn through guided tours,” Mitchell said. “They are learning that through tactile objects, they can touch and get information.”

Mitchell has never heard of the proposed cuts to the centre and said staff are always working hard because they need to help people understand history better.

Last April, the National Park Service promoted $23.4 million grants for 39 projects aimed at preserving sites and stories about African American efforts to fight for equal rights.

Over the years, the National Park Service has evolved primarily with a focus on nature and parks, including sites with a rich history, Mitchell said.

“We realized as a worship service that there are tentacles in history,” she said.

“You want people to know history.”

The Reidy family studied maps outside the Underground Railroad Visitors Centre looking for other Tubman sites to explore.

Tim and Kim Lady took their children Elizabeth and Sam to the center to learn more about Tubman. They were on a spring break trip from Westchester, New York.

“It seemed like an important, historically relevant aspect of the place’s history,” Kim Reidy said.

Elizabeth, 15, learned about Tubman at school, and she said “it’s very important to dedicate the museum and these spaces to this.”

Tim Reedy said the family might visit Tubman Centre in Auburn.

“Reading about it is one thing, but being in a real physical space is a completely different experience,” he said. “You can see why people want to come here. You don’t want to lose that.”

Ronda Miller and daughter Madison of Bowie, Maryland, followed when director Mitchell led them on the tour of the Tubman Center.

Miller and other members supporting parents, a support group for parents of children with special needs, traveled to the center for two hours.

Miller learned the basics about Tubman, her and Madison, watching the 2019 film Harriet.

“This was built on top of it and I was going to see where she might have actually walked,” Miller said. “I love the way they put this museum together and presented information. It was truly amazing.”

Miller said in an effort to erase black history, Madison also said it was particularly important to learn about it outside the classroom.

“I hate seeing places like this disappear,” Miller said after the visit. “We need them.”

“Treat our history with respect.”

A few miles from the center in downtown Cambridge, William Germon attracted visitors to the Harriet Tubman Museum and Education Center to share her history. Tubman enslaved the first 27 years of her life in this area.

The small museum featured portraits of the Tubman and the exhibit. A mural of Tubman reached out was painted on the side of the building.

There are other nods to Tubman’s heritage within the county, including statues outside the courthouse.

Germont, president of the Harriet Tubman Organization, the nonprofit that runs the museum, said it relies in part on local support to continue the tours and missions it offers.

“We make the business of reaching all generations, especially through school, so they make sure they understand that it’s not her story, but that’s all about us,” Jarmon said.

Institutions that receive federal funds feel pressured to roll back their diversity programs, Stephenson said.

The Equal Justice initiative has three sites in Montgomery, Alabama, focusing on black experiences, including a new sculpture park. The program is personally funded.

“I hope this is a short-term issue because the majority of people in Congress really believe they don’t want to refund our major museums and institutions without agreeing to all the sentences in those museums,” Stevens said.

Some groups, including faith leaders, have stepped up to teach more black history.

Cliff Albright, co-founder of Black voters, said others are increasing support for Black museums and programs. Still, he said that history should be included in taxpayer-funded institutions.

“Our hope is that even though some of us are looking for ways to ensure that history is maintained, they treat our history with the respect they deserve it,” Albright said.

These efforts should not be held back, Stephenson said.

“What we shouldn’t do is retreat from true-talking, honest and accurate history, providing a complete story,” he said. “It’s a disaster recipe to cultivate ignorance.”