The Supreme Court has allowed the education sector to proceed with a massive layoff while the court battle was raging. However, not all firing was technically reversed.

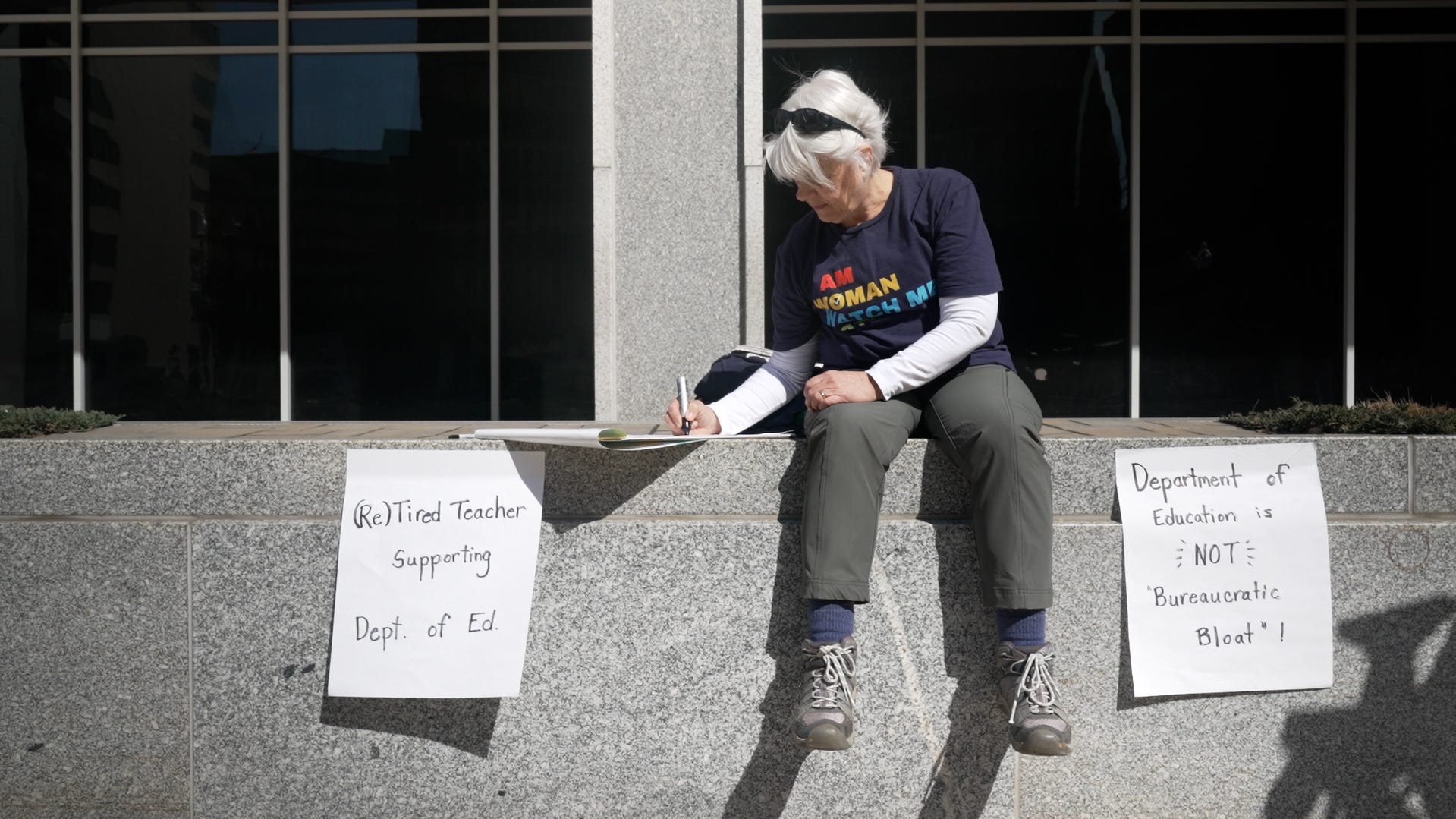

“Make Me cry”: Teachers and students respond to reductions in the Department of Education

Former students and teachers have responded to Trump administration’s funding cuts and layoffs at the Department of Education.

Washington – It seems like Beth German Beer is waiting for things to do these days.

First, she was waiting to see if President Donald Trump would follow his promise to dismantle the U.S. Department of Education. She has worked there for nearly 20 years, preventing students from experiencing bullying that she grew up with disabilities.

Then in March she and more than 1,300 colleagues were fired and waited for the court to see if they would intervene. By May, a federal judge in Boston had revived her position and the position of many of her colleagues.

Now she’s in Limbo again. On July 14, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the Trump administration to continue the massive education department layoffs while the lawsuit was underway.

In the days after the order, Germane Beale and other fired workers expressed disappointment at the decision, but most were not surprised by it.

They warned that this was the result of some schools and students already suffering after the layoffs got worse. The important information that teachers rely on to make decisions is already at risk. University financial aid could face more confusion. And it’s not clear that there is the personnel needed to smoothly implement the education provisions of President Trump’s main tax and spending laws.

Regardless of these concerns, the president was delighted with the ruling. In a social media post, he celebrated it as a “big victory.”

“The federal government operates our education system on the ground,” he wrote. “But we’re going to turn it all around by giving people back to their strength.”

Civil rights lawyers escaped the verdict

Gellman-Beer is in a unique situation. Technically, she still has her job.

Her position was protected by another court order, particularly in another case, in order to revive education department staff who were fired at the Civil Rights Office. The OCR works to resolve allegations of discrimination and harassment brought about by students and teachers in colleges and K-12 schools, as Gellman-Beer calls it.

The entire regional office she led in Philadelphia was among the seven people Trump closed in March. Hundreds of OCR staff have been let go.

She has struggled to explain her life ever since. “The Endless Unknown” was a phrase she used. “The roller coaster of emotions” was something else.

“We need to move to the next stage of our career,” she said.

In a court filing on July 15, Rachel Ogresby, the Education Department’s Chiefs of Staff, confirmed that the agency is still working to get staff back to the Civil Rights Office.

Scotus orders “heartbreaking hurdles,” says fired workers

Politics and logistics closing the education sector is complicated.

Education Secretary Linda McMahon admits that Congressional approval and therefore Democrats’ help is needed to do so. Still, she is testing boundaries. The day after the Supreme Court order, she announced a partnership that would allow the Federal Labor Bureau to support the responsibilities of a small number of education departments.

Despite President Trump’s claims, he has given it a lot of new responsibility, despite the insistence that the agency must close. His tax and expenditure law creates several new student loan repayment programs and a new university accountability system.

To enforce the law, the education department will need many of the same type of people who just removed it, said Robert Jason Cottrell, data coordinator for the Post-Secondary Education Department.

“My biggest fear is that they try to conclude something like this in order to get it done,” he said. “I don’t know if that will work.”

Rachel Gittleman, who was fired from the department in March, is most concerned about how student loan borrowers are affected. She worked for the Federal Student Aid Office, a branch of an institution that oversees the US nearly $2 trillion student loan portfolio.

Her department lost most of the workers in layoffs. Since then, despite the worrying confusion observed in the financial aid system, she has comforted the fact that the legal battle ahead is long.

“This is a devastating and heartbreaking hurdle,” she said. “But the battle isn’t over.”

Zachary Schermele is an education reporter for USA Today. You can contact him by email at zschermele@usatoday.com. Follow him on X at @Zachschermele and follow Bluesky at @Zachschermele.bsky.social.