Milwaukee

–

The library at Starms Discovery Learning Center features hilarious peaches and blue walls, and squat wooden shelves filled with books wrapped in thick plastic jackets to protect them from the touch and dirt of many small hands.

On Monday, the library was also a place to exchange other stories – a dark story. These were stories of stressed mothers and insecure children, and the fifth-grade alumni who missed the end of the year celebration.

The story was about a family with dangerous toxins (lead) in their homes and now in public schools. Those families We shared stories about brain damage and learning disabilities, and the federal government that denied them.

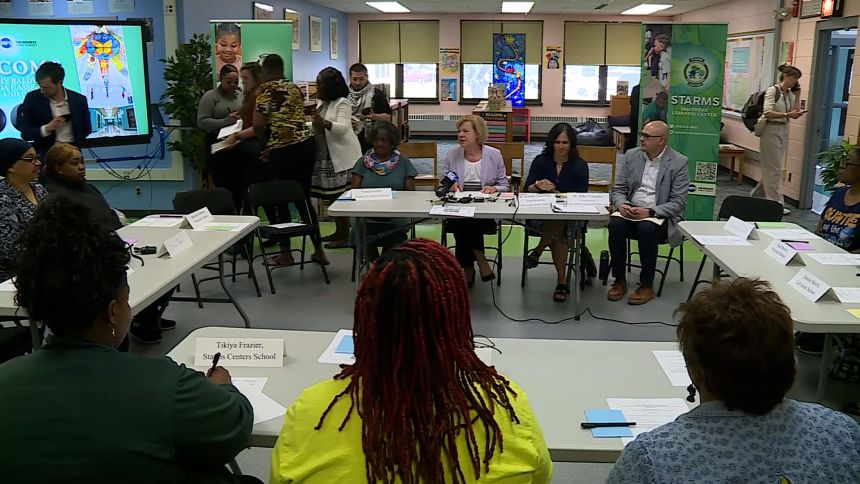

“I’m here to elevate your story,” said Sen. Tammy Baldwin, a Democrat from Madison, a Wisconsin Senator.

Baldwin, adjacent to the city’s health department and school district officials, has come to the stars to meet family and community activists to hear more about their lives since the discovery that their children were poisoned by stripping lead paint in one of the city’s aging and unmaintained school buildings.

The city’s health department ordered the district to correct the danger, but the scope of the issue turned out to be much larger than a single building. So far, the district has closed six schools for cleaning and repainting, driving away around 1,800 students. Over the summer, the district’s efforts will be high gear. The goal is to visually inspect all school buildings by September 1st.

Wisconsin’s largest district has 144 buildings. All but 11 were built before 1978, but it was still legal to use leads in paint. The average age at MPS school is 82 years old.

A few blocks away, the Starms Early Childhood Center, the elementary school’s sister campus, is one of four that remains closed. Built in 1893, the kindergarten and kindergarten students and their teachers were moved to elementary school. The city has cleared the building to reopen, but many families said they prefer to stay where they were until the end of the school year to minimize further disruption. Friday is the last day in the district before summer vacation.

Several students in the district have found that their blood lead levels are elevated. One case is clearly linked to the deterioration of paint in Golda Meir Elementary, the basement of the school building. Students were involved in the other two cases Trowbridge and Kagel Schools. The investigation determined that the source of the lead was probably a combination of exposures from home and school.

Caroline Reinwald, a spokesman for the Milwaukee Health Department, said other cases were being investigated and the school was cleared as a source of information.

Since the crisis began, Reinwald said about 550 children have been screened for Lead at a clinic run by the Ministry of Health and Novill, a company hired by the city to help with screening. This does not include children who may have been tested through a primary care physician.

“We need to test more kids on leads,” Milwaukee Health Commissioner Dr. Michael Torratis said Monday.

The Milwaukee City Health Department was working with experts for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention when the entire team was fired in April for reducing federal power cuts.

The city had requested CDC dispatched disease detectives to help implement a wide range of blood test campaigns for children at city schools. The request was also denied, with the agency citing the loss of a key expert.

Families attending the meeting with Baldwin said they were furious at the Trump administration’s apparent lack of support or interest.

“The kids need to be protected now,” said Tikiya Frazier, who has nie and nephew in two closed schools. “We understand that and help them. This is an emergency for us.”

On Monday, Baldwin issued an invitation to US Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who visited Milwaukee and saw and heard about his problems. She has twice before pushing Kennedy about denial of federal aid. In both cases, he gave a breathtaking answer.

“Are you going to eliminate this brunch at the CDC?” Baldwin asked him at a hearing in May.

“No, I won’t,” Kennedy replied.

However, he has not yet revived fired experts or resumed the lead program for a healthy America under his planned administration. He is also not given a timeline for cases where federal lead poisoning prevention efforts may continue.

When Baldwin asked Kennedy about the situation in Milwaukee at a budget hearing a week later, he replied, “We have a team in Milwaukee.” The team is a lab engineer and has helped temporarily calibrate machines at the city’s public health lab.

The city has been demanding and needing that help for years, but authorities said it is not the job they have asked the CDC to work on recently.

“He was lying or not knowing what was going on with his agency. Either one of them is unacceptable,” Baldwin said after Monday’s meeting.

Kennedy also failed to respond to a letter sent in April by Baldwin and U.S. Rep. Gwen Moore, urging them to revive the CDC lead team.

On Tuesday, Baldwin and her colleague, Sen. Jack Reed of Rhode Island, sent another letter to Kennedy asking detailed questions about the fate of the lead poisoning prevention program. They responded to him until June 16th.

“We have to hold the Trump administration accountable,” Baldwin said. “They were able to improve what’s going on today by rehiring these experts.”

CNN contacted the HHS and the White House to ask questions about plans for a lead poisoning prevention program and get the administration’s response to Milwaukee parents. HHS did not respond at CNN deadline.

“Wisconsin is always there for other states so it’s mad,” said Core Branch, which has four children at Milwaukee public schools.

When tap water in Flint, Michigan tested positive for high levels of leads a decade ago, Branch said he remembers community members cramming food and supplies for help. But now, “Where is our help? Where is our help?”

When it closed in early May, Branch had two sons at West Side Academy. She was sent home with her children and was notified in a newsletter later sent over the phone.

“My anxiety hit the roof,” she said.

The district either moved classes to Andrew Douglas Middle School about three miles away, or gave students the option to take classes online.

Brunch says her carefree 5-year-old Jonas took things boldly, but Jeril, a sensitive 10th grade fourth grade, was unable to handle the change.

“I had to choose. I had to separate the two,” Branch said. Jonas moved to a new campus with his class and teacher, but Jarrell took classes online after returning home from work in the evening.

“I can’t speak for everyone else, but that highlighted my home,” she said.

Branch said her child has a vigilant pediatrician who tested the lead on her annual wellness visit. So far, their test results have been normal. Still, she had planned to take her youngest to a local church free clinic to take her test again.

Santana Wells said he had a son and nie attending fifth graders at Brown Street Academy, which closed on May 12, about a month before school was over.

Being at another school left her son missing out on many of the activities he had planned for the fifth graders on Brown Street, she said..

“Brown Street did carnivals every year. They do picnics. They have a long list of what they were doing for their alumni,” Wells said. Now she said, it was a freed field trip and felt it was unfair.

Wells said he would “run a strict schedule” from home to work by 3pm every day. With the changes in school, her son had arrived at home. After that, she slowed her down, on top of everything else.

Several parents felt that their children were questioning about the lead and were worried about returning to school in the fall.

The story told Monday wasn’t just about the federal government’s ears. Totoraitis said questions from the children were also a light bug moment for him. Health Department workers were very careful to explain Reid’s situation to parents, but they didn’t do much to answer the child’s questions about what was going on. He said the department would work on it.

He also wants to temporarily hire at least one of the laid-off CDC lead experts for weeks to review the city’s efforts and make sure they are on track.

Baldwin hopes the federal government will also rehire them.

“These are well-known experts in lead mitigation and restoration as children, like we did in Flint, Michigan, and the federal government needs to have the ability to support that staff,” she said. “That’s what we need now here in Milwaukee.”

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency lifted an emergency order on drinking water in Flint last month.