Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory Science Newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific advances and more.

New research shows that some of the most widely known archaeological discoveries of all time may have been considered once.

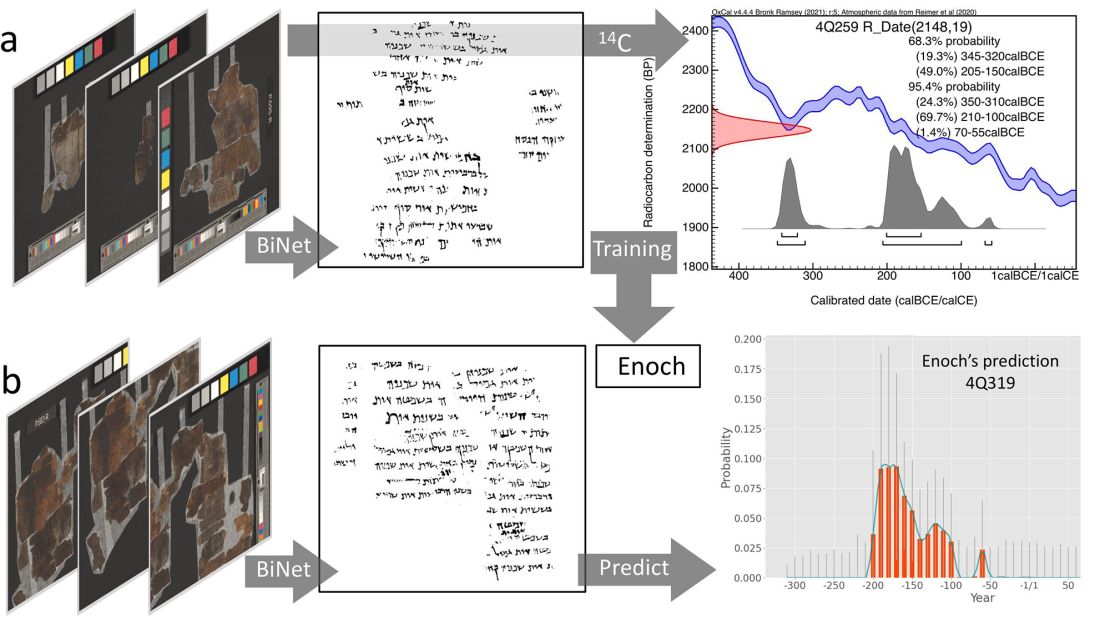

A fresh analysis combining radiocarbon and artificial intelligence was determined by some of the Bible manuscripts around 2,300 years ago when their estimated authors lived, said Mladen Popović, the lead author of the report, published Wednesday.

A Bedouin shepherd accidentally found a scroll in 1947 in the Jewish desert near the Dead Sea. Archaeologists subsequently retrieved thousands of fragments from 11 caves, belonging to hundreds of manuscripts.

Popovich, who is also the dean of the Faculty of Religion, Culture and Sociology at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, said, “The scroll of death was very important when it was discovered. “Of the approximately 1,000 manuscripts, over 200 what we call the Old Testament of the Bible, is the oldest copy of the Hebrew Bible. They gave us a lot of information about what texts looked like at the time.”

According to Popovich, the scroll is like a time machine. Because they let scholars see what people were reading, writing, and thinking at the time. “They are physical and concrete evidence of important historical periods, whether you believe that you are a Christian or Jewish at all, because the Bible is one of the most influential books in the history of the world, so the scrolls allow you to study it as a form of cultural evolution,” he said.

Most of the Dead Sea scrolls written primarily in parchment and papyrus Hebrew are dated on them. Based primarily on ancient works, ancient writing and research and deciphering manuscripts, scholars believe that manuscripts range from 3rd to 2nd centuries BC. “But now, in our project, we already have to date some manuscripts until the end of the fourth century BC,” he said. In other words, the earliest scrolls can be up to 100 years older than previously thought.

“This is really exciting as it opens up new possibilities to consider how these texts are written and how they moved to other users and readers outside the original author or social circle,” Popovich added.

The findings, according to the report’s authors, not only encourage further research and affect historical reconstruction, but also unlock new prospects in the analysis of historical manuscripts.

Previous estimates of manuscript age came from radiocarbon dating carried out in the 1990s. Chemist Willard Libby developed this method at the University of Chicago in the late 1940s. It is also known as carbon 14 dates, a chemical analysis of samples such as fossils and manuscripts, which determines the amount of carbon 14 atoms contained. All living creatures absorb this element, but they begin to decay as soon as death occurs. So, looking at how much remains, we can give a fairly accurate age of organic specimens about 60,000 years.

However, carbon dating has its drawbacks. The analyzed samples are destroyed during the process, and some results can be misleading. “The problem with the previous test (scroll) is that they didn’t address the castor oil issue,” Popovich said. “Castor oil is a modern invention, used by original scholars in the 1950s, making the text more readable. However, it is a modern contaminant, distorting the results of radiocarbon to a much more modern date.”

The research team first used new radiocarbon dating and applied modern technology to 30 manuscripts. Only two were young.

Researchers then trained an AI called Enok after a biblical figure, the father of Methuselah, using high-resolution images of these newly-dated documents. Scientists presented Ennoch with more documents they made carbon carbon, but withholding dating information, AI correctly guessed 85% of the time according to Popović. “In many cases, AI narrowed the date range for manuscripts than carbon14,” he said.

Next, Popovich and his colleagues gave Ennoch more images from 135 different death scrolls that were not dated with carbon, and asked the AI to estimate their age. Scientists rated the results as “realistic” or “unrealistic” based on their own archaic experience, and found that Enoch had realistic results for 79% of the sample.

Some of the manuscripts for this study were found to be 50-100 years older than previously thought, Popovich said.

One sample from a scroll known to contain poetry from the Book of Daniel was once believed to have been up to the second century BC. “It was a generation after the original author,” Popovich said.

Another manuscript is also older, with poems from the evangelistic book, Popovich added. “The manuscript was previously dated for classic reasons from 175 to 125 BC, but now proposes 300-240 BC,” he said.

Ultimately, artificial intelligence could potentially replace carbon-14 as a way of dating manuscripts, Popovich suggested. “Carbon 14 is destructive,” he said. “Because we have to block out a small part of the Dead Sea scroll and it’s gone. It’s only seven milligrams, but it’s something we still lose. At Enoch, we don’t have to do this, which has all sorts of possibilities to further improve Enoch.”

As the team advances the development of Enok, Popovich believes it can be used to evaluate scripts such as Syrian, Arabic, Greek, and Latin.

Scholars not involved in this study were encouraged by the findings.

Having both AI and extended carbon 14 dating methods allows for level calibration across both methodologies that help, according to Charlotte Hempel, professor of Hebrew Bible at the University of Birmingham in the UK and professor of Judaism at the Second Temple. “The prominent pattern seems to be that AI offers narrow windows within carbon 14 windows,” she said in an email. “I think this suggests a higher level of accuracy. It’s very exciting.”

Lawrence H. Schiffman, a globally renowned Professor of Hebrew Language Studies at New York University’s Hebrew and University of Jewish Studies, said the study represents the first attempt to leverage AI technology.

“To some extent, it is not yet clear whether the new method will provide reliable information about texts that are not yet dated for Carbon-14,” he added in an email. “Interesting comments on the dating of some manuscripts expected by this approach and further development of new Carbon-14 dating are not new to this study, but constitute a very important observation in the field of general death scrolls.”

Commenting on the computational aspects of the study, Brent Shields, a graduate of the University of Kentucky, said the approach the authors adopted would appear to be tough, even if the sample size was small.

However, it may be premature to completely replace carbon dating using AI. “(AI) is a handy tool for making estimates in the absence of carbon-14 based on witnesses of other similar fragments,” Seales wrote in an email.

“Like machine learning, and fine wine, dating ancient manuscripts is a very difficult problem, with scope constraints on access and expertise.