Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory Science Newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific advances and more.

CNN

–

The sensitive interior of human teeth may have originated from a seemingly unlikely location. It is the sensory tissue of a fish that swam in the Earth’s oceans 465 million years ago.

Our teeth are covered in hard enamel, but the dentin – the inner layer of the teeth involved in carrying sensory information to the nerves – responds to changes such as intense biting, pain, or extreme cold or sweetness.

When trying to determine the origin of teeth, one of many possibilities that researchers have considered over the years was that teeth may have evolved from the ridges of the armored exoskeletons of ancient fish. However, the true purpose of the structure called Odontodes was unknown.

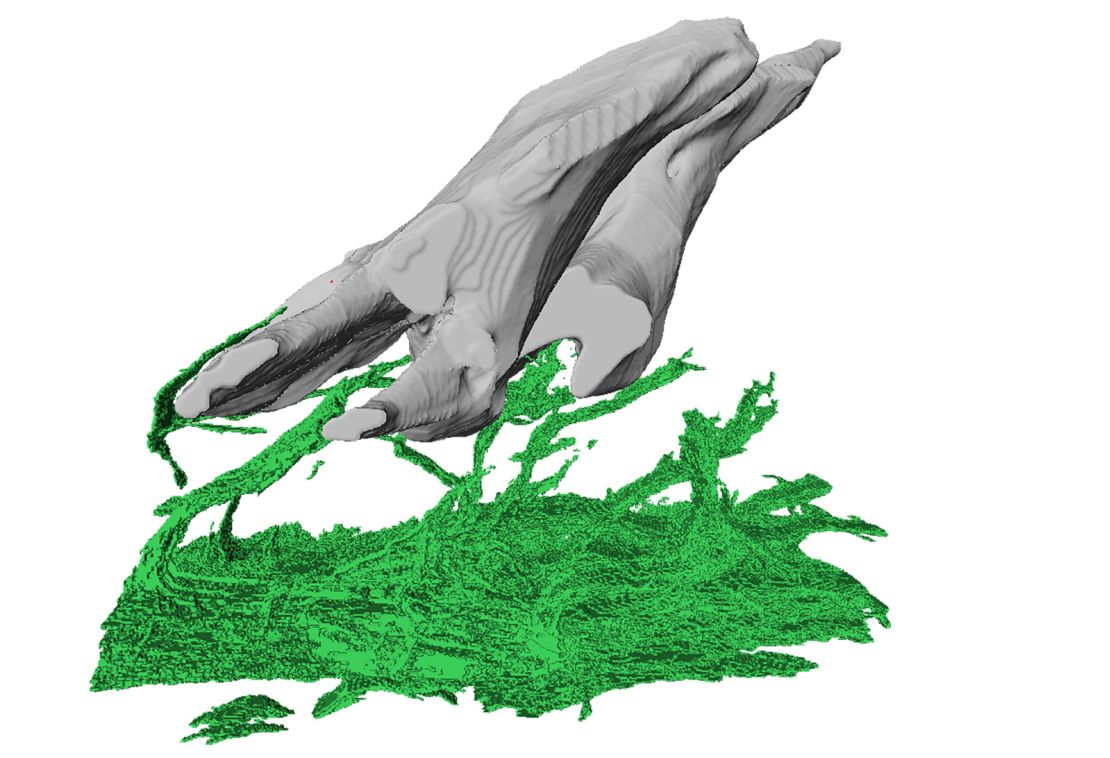

Now, new research into fossils and 3D scans have provided evidence that external uplifts contain dentin. Scientists reported the findings of the nature magazine on Wednesday.

“It’s covered in these sensitive tissues. Maybe when you hit something, it can feel that pressure. Or when the water gets too cold and you need to swim elsewhere,” Dr. Yara Harudy, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Chicago’s Department of Biobiology and Anatomy, said in an email.

During its analysis, the team also revealed similarities between dental similarities and features known as sensella, which exist as sensory organs present in the shells of modern animals such as crabs and shrimp, and can be found in fossilized invertebrate arthropods. The development of teeth in vertebrate fish and the development of arthropod sencira are representative examples of evolutionary convergence when similar features evolve independently in different animal groups.

“These jawless fish and agraspizid arthropods (extinct marine arthropods) have very distant shared common ancestors and may not have any hard parts at all,” Khalidi said. “We know that vertebrates and arthropods have independently evolved their stiff parts and, surprisingly, similar sensory mechanisms that are integrated into the rigid skeleton.”

While arthropods retain their senses, the dental proteophyte appears to be a direct precursor to the animal’s teeth.

They reached another discovery as researchers compared Sensera to Odontode. One species once thought to be an ancient fish was actually an arthropod.

Khalidi’s original purpose was to solve the mysteries of the oldest vertebrate animals present in the fossil record. She approached museums across the country and asked if she could scan fossil specimens from the 540 million-year-old Cambrian to the 485 million-year-old Cambrian period.

She then settled thoroughly in the Argonne National Laboratory, capturing high-resolution computed tomography (CT) using advanced photon sources.

“It was a night at the particle accelerator. It was fun,” Khalidy said.

At first glance, the fossils of anatrepis, known as the anatrepis, looked like vertebrate fish. In fact, a previous study in 1996 identified it as one. Khalidi and her colleagues noticed a series of pores filled with material that look like dentin.

“We were digging each other high. “Oh, my god, I finally did it,” said Haridi. “It would have been the first tooth-like structure of vertebrate tissue from the Cambrian era. So we were pretty excited when we saw the bright signs of what looked like dentin.”

To confirm their findings, the team compared scans of other ancient fossils with scans of modern crabs, snails, beetles, sharks, barnacles, and even catfish from miniature soccer trout that Khalidy had raised himself.

These comparisons showed that Anatrepis is similar to arthropod fossils, including those from the Milwaukee Public Museum. And what the team thought was a tubule lined with dentin was actually similar to Sensila.

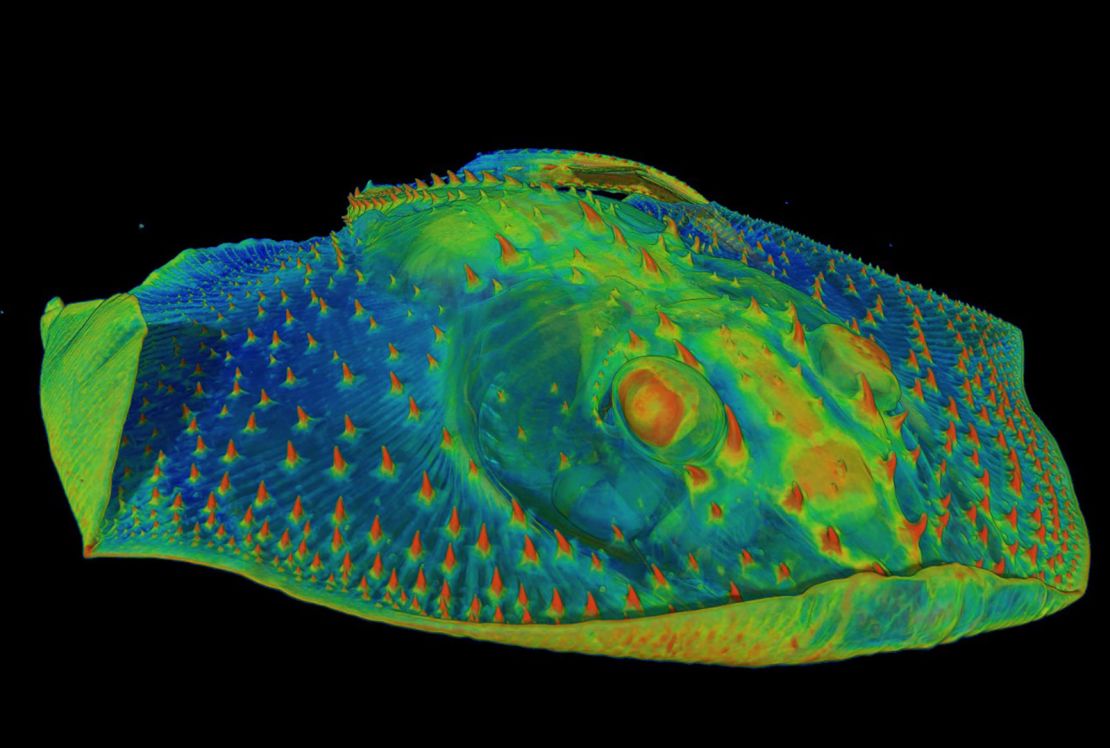

However, during their scans they found dentin-containing dentin in ancient fish such as Ellipticus and Astraspis.

The confusion over the true nature of Anatrepis came from the fragmentary nature of the fossil. According to Harudy, the most complete piece is only 3 millimeters (0.1 inch), which has proven to be a comparative study challenge that relies on external imaging.

However, the new scans she conducted allow the fossils to be seen in 3D, revealing the internal anatomy.

“This shows that even if the ‘tooth’ is not in the mouth, it’s sensory,” Khalidi said. “So these fish have sensitive armor. These arthropods have sensitive armor. This explains the confusion with these early Cambrian animals.

The cutting edge modern imaging used in the study solves the discussion about Anatrepis, said Dr. Richard Dirden, a postdoctoral researcher at the Naturis Center for Biodiversity in Leiden, Netherlands. Dearden was not involved in the new research.

“The (research author) uses cutting-edge modern imaging approaches to try and solve this question, assemble impressive comparative data, and convince and establish that Anatrepis is not actually a vertebrate,” Dearden said in an email.

Armored jawless fish such as Astraspis and Eriptychius, and ancient arthropods such as Anatolepis coexisted in muddy Ordovician waters that occurred between 485.4 million and 443.8 million years ago.

Other contemporaries of these animals included large cephalopods such as giant squid and huge seabeds. Characteristics such as Odontodes and Sensilla help fish and arthropods distinguish predators and prey.

“When you think about these early animals, when you’re swimming in armor, it needs to sense the world. This is a rather intense, predatory environment, and it would have been very important to be able to sense the water properties around it.” “So here we see that armorless invertebrates, like horseshoe-shaped crabs, also need to sense the world.

Some modern fish have teeth, but sharks, skates and some catfish are covered in small toothlets called dentists, and the skin feels like sandpaper, says Halidy.

Khalidy studied the catfish tissue she raised and noticed that the dentist was connected to the nerves just as the teeth were in animals. When comparing teeth, teeth and sencira, they were all incredibly similar, she said.

“We think that the earliest vertebrates, these big armored fish, had very similar structures, at least morphologically. They all create this mineralized layer that covers soft tissue and helps to sense the environment, so they look the same in ancient and modern arthropods,” Khalidi said.

According to the study authors, the genes needed to form teeth may have later produced animals-sensitive teeth, including humans.

The findings supported the idea that sensory structures first appeared in exo skeletons, providing genetic information that can be used to create teeth as they become a necessary part of life, the study authors noted.

“As time passed, fish have evolved their jaws and have an advantage in having pointy structures around and in their mouths,” Khalidi said. “A little by little, the fish with jaws has pointy keratinous keratin at the end of its mouth, which ultimately existed directly in the mouth and was lost throughout the body. The relationship between teeth and teeth is continuously revealed by new fossils and modern genetics.”

The new research is improving the timeline of the first appearance of hard tissue and the early ancestors of jawed fish by removing anatrepis from fish tree trees, said Dr. Lauren Saran, assistant professor at the Macro Evolution Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan. Saran, who was not involved in the new study, also raised an interesting new hypothesis that precursors like the tooth scaleri evolved to detect prey, friends, or water predators.

“This is a real challenge to the seemingly obvious assumption that it has evolved (mainly) for hard tissues like dentin and for body protection and throat feeding,” Saran said. “It could have been “up” (and subsequently modified) for these uses instead. It’s just like how limbs evolved before walking on track. It is also interesting to see the extent of convergence between early armored arthropods and fish, and also to raise questions about how much ecological overlap occurred between these two groups. ”

Khalidy wants to continue his search for fossils that could lead to the oldest vertebrates, given that researchers expect to have more early vertebrates than Astraspis and Ellipticus. And despite not discovering it through the study, they made valuable discoveries, Shubin said in an email.

“I was disappointed that (Anatrepis) was not a vertebrate, but I was surprised by the new ideas that arose,” Shubin said. “And that took us in a whole new direction. It’s science.”