Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory Science Newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific advances and more.

CNN

–

Immunologist Jacob Granville came across media reports in 2017 about men who injected hundreds of times the venom of the world’s deadliest snakes, including cobras, manbus and rattlesnakes.

“The news article was a bit flashy. “The crazy guy puts a little hand on the snake,” Granville said. “But I could see it, and I seemed to have diamonds in the rough here.”

Granville Diamond is a self-taught snake expert based in California, and has been exposed to snake venom for nearly 18 years, effectively gaining immunity to several neurotoxins.

“We had this conversation, and I know it’s annoying, but I’m really interested in seeing some of your blood,” recalls Granville. “And he said, ‘At the end, I was waiting for this call.’

The two agreed to work together, and Friede donated a 40ml blood sample to Granville and his colleagues. Eight years later, Granville and Peter Kwon, Dr. Richard J. Bazillos and Professor of Medical Science at the University of Surgeons published details of the anti-toxicity that could protect against bites from at least 19 venomous snakes, based on Friede’s blood antibodies and Venom blocking drug antibodies.

“Tim, to my knowledge, he has an unparalleled history, which was a very diverse species, different from all continents where snakes are.

“But we are all very discouraged to try and do what Tim did,” Granville added. “Snake venom is dangerous.”

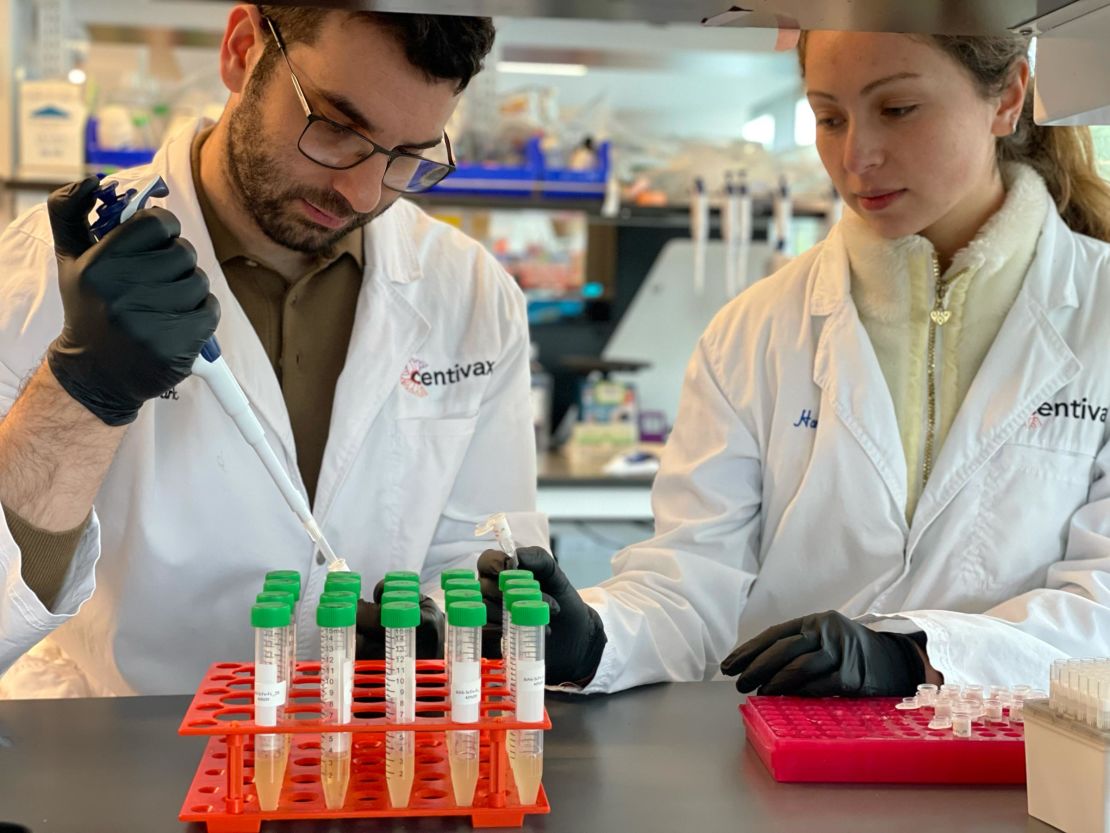

Friede gave up on vaccinating snake poison in 2018 after several close calls and is currently employed by Granville biotechnology company Centivax, Granville said. Glanville is CEO and Chairman of Centivax.

The study was published in the Science Journal Cell on Friday. CNN contacted Friede, but he did not respond to the interview request.

If you are unlucky enough to sink a venomous snake into you, your best hope is anti-venom.

Traditionally, this process involves milking the snake’s venom by hand and injecting it into the horse or other animal to evoke an immune response. The animal’s blood is drawn and purified to obtain antibodies that act on the poison.

Production of anti-products in this way can be messy, let alone dangerous. This process is error-prone and cumbersome, and the completed serum can have serious side effects.

For a long time, experts have been sought a better way to kill about 200 people per day, mainly in developing countries, and about 200 people a day with disabilities. The World Health Organization added Snakebite to its list of neglected tropical diseases in 2017.

Granville grew up in rural Guatemala, but said he had known for a long time the health issues brought on by Snakebitt, and quickly realized that Friede’s experience presented a unique opportunity.

Exposing snake venom for nearly 20 years by injecting venom and allowing it to bite, Friede has produced effective antibodies at once against several snake neurotoxins.

Researchers isolated antibodies from Friede’s blood that reacted with neurotoxins found in 19 snake species tested in studies including coral snakes, mamba, cobras, taipan, and craite.

These antibodies were then tested one by one in mice poisoned with poison from each of the 19 species, allowing scientists to systematically understand the minimum number of ingredients that neutralize all venom.

The drug cocktails the team created ultimately contained three things: It is a small molecule drug varespladib that inhibits two antibodies isolated from Friede and enzymes present in 95% of all snake zones. The drug is currently undergoing clinical trials for human clinical trials as a standalone treatment.

The first antibody, known as LNX-D09, protected mice from lethal doses of the venom from six snake species.

The addition of Varespladib gave protection against three additional species. Finally, the researchers added a second antibody isolated from Friede’s blood called SNX-B03, expanding protection with 19 species.

Anti-vivenom provided mice with 100% protection against 13 venoms and partial protection (20%-40%) for the remaining six people, the researchers said.

Stephen Hall, a snake pharmacologist at Lancaster University in the UK, called it “a very clever and creative way” and developed the antivenom. Hall was not involved in the study.

And although the cocktail has not been tested in humans, if approved for clinical use, Hall said that the human origin of the antibodies is likely to mean fewer side effects than antivenoms made traditional methods using horses and other animals.

“This is impressive for the fact that it is done with one or two antibodies and small molecule drugs, increasing the number of species compared to the usual antidotes.

“When it reaches the clinic, it becomes people in the long run, but it’s innovative. In fact, it’s going to completely change the field from a snake bite perspective,” he said.

Columbia’s Kwon said the published research focused on a class of snakes known as elapids. Viperids, another major group of venomous snakes, including rattlesnakes, sawed vipers and additional species, were not included.

However, the team is investigating whether additional antibodies identified in Friede’s blood or other drugs could provide protection against the viperide family of this snake.

“The ultimately contemplated product could be a cocktail protested against a single bread, or potentially creating two, one for the Elapids, and the other for Viperids, as they only have a portion of the world,” Kwong said.

The team also wants to start field research in Australia. In Australia, only snakes exist, allowing anti-toxicity to be used in dogs bitten by snakes.