Luka Krizanac’s phone has a video showing her making coffee at home using an espresso machine. This is the type of video that anyone might take to show off their new gadgets to friends or recommend a bag of favorite beans. But normality is truly extraordinary for Krizanak. Because he had no hands a few months ago.

Krizanac lost part of his arm and leg at the age of 12 after a mismanaged infection led to severe complications requiring sepsis and amputation. Almost 17 years later, last fall, he underwent a double manual implant at Penmedicine.

Hand transplants are rare. According to one study, as of mid-2023, only 148 people were performed worldwide, not all of which were double transplants.

More than 20 people were involved in Krizanac’s surgery, lasting for about 12 hours and following years of practice.

As the anesthesia was worn out, Krizanak turned to one of the nurses at his bedside and said, “Look at how beautiful my hands are.”

He does not remember the moment – it was later told to him by the nurse – but deep emotions remain.

“I don’t mean it’s an aesthetic way, it’s a deep sense of being fully as a person again,” he said.

For Krizanac, living without hands was more challenging than living without legs. The hands are necessary for thousands of essential everyday things, and the prosthetics he couldn’t meet the needs as much as the prosthetics he had on his feet, he said.

“The question is, ‘What can you not do?’ It’s, ‘How can you live?'” he said. “I walk on my feet. I do thousands of things, from eating with my hands to caring for myself, cooking, to expressing myself. So it’s impossible to try and make up for my lack of arms with the hands of a plastic robot.”

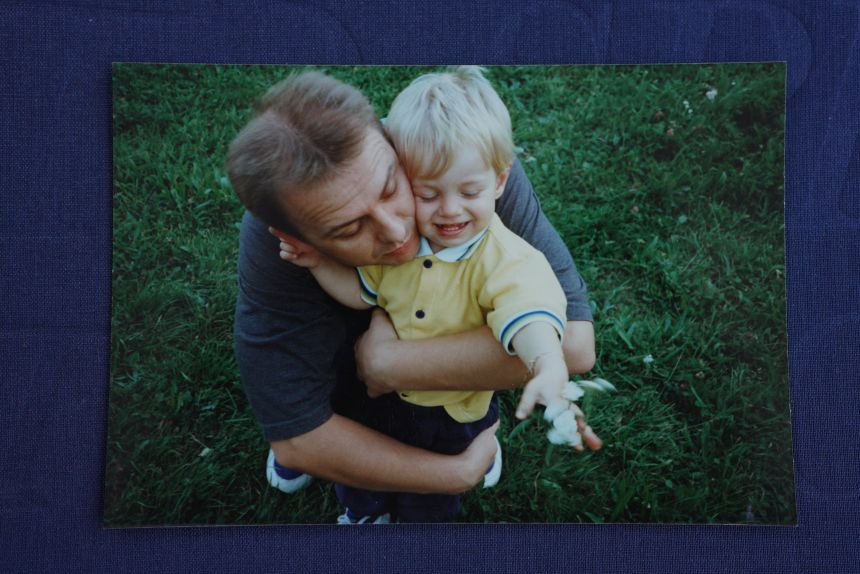

The childhood he knew before he was present faced with the loss of independence, relying heavily on the strong support of his beloved family and friends.

“As you grow, you want more independence. Naturally, as humans, we should be independent as we grow,” Krizanak said. “I couldn’t achieve that, so the need for it definitely increased over time.”

Krizanac gave up not letting his obstacles define him and maintained a positive outlook by trying to live in the present, but he and his family continued to look for ways to improve the quality of life.

They have been pursuing hand transplants for many years, but many obstacles have been stuck, including insurance coverage and lack of access to skilled providers.

“I knew there was a solution for my problem. The problem was how to get to that solution,” Krizanac said.

In 2018, about a decade after he lost his hand, a series of accidental connections brought Clizanac from his Swiss home to Dr. L. Scott Levin’s office in Philadelphia.

Levin, honorary chairman of the Orthopedics Department and professor of plastic surgery at Penn Medicine, was immediately impressed by Krizanac’s calmness and was soon loved by the entire team.

“For a variety of reasons, he was a great candidate for hand transplants,” Levin said. “He fulfilled all traits: intelligent, informed, incredible family support.”

However, other challenges have been further delayed, including the global pandemic and wounds that developed in Krizanac’s feet.

“We had to put things on hold during the pandemic,” Levin said. “And he would not have been allowed to have his hand implant because he had an open wound and a skin breakdown (of the legs), which prevented us from moving forward with the risk of open wounds and infection.”

However, Levin and his colleagues flew to Switzerland to treat their feet and then returned to Philadelphia while Clizanac was healed, then jumped into preparations for a hand transplant.

Preparation for a double-handed implant generally takes about two years, except for other complications. But by the second half of 2024, Levin and his team were ready. They completed over a dozen rehearsal sessions and mapped the complex steps needed to mix nerves, muscles, blood vessels and bones.

Krizanac moved to Philadelphia and did his best to enjoy his stay while waiting for updates.

The call took place about two months later on a rainy Sunday afternoon. There was a match. Life of Life, an organ donation program, has found donor hands from people with the right skin tone, size and gender.

Within a few minutes, Krizanak was packing up and heading to the hospital, and he was in the room within an hour.

“When you decide over the years something is right and decide to work towards this goal, you get a green light, you have no idea,” Krizanak said. “I had no reservations on this process. I was sure 17 years later I knew what was right for me.”

A well-organized team of plastic surgery, orthopedic surgery, transplant specialists, anesthesia and nursing, worked simultaneously with Krizanac and donor.

After suturing the vessels together, circulation was monitored with various devices. The nerves take longer to regenerate, so it was impossible to know whether that part of the surgery was successful in the operating room.

“We rely on our nerves to regenerate, but that’s not guaranteed. All we can do is technically best fit and the best nerve repair that can do a day of injury with incredible accuracy using a surgical microscope,” Levin said. “If you’re a little lucky, carefully plan and execute the operation and the nerves from the donor will grow into the muscles.”

Today, Krizanac is very well healed, Levin said. The nerves continue to grow in his arms, and his recovery will continue to evolve over the next few years.

“The ability to sense and feel will improve. His strength will be greater. He will begin to regain the fine muscles in his hands,” Levin said. “He’s on track. Of all the transplant patients we’ve seen, his nerve recovery is the most accelerated.”

In addition to three or four physical therapy sessions each week, Krizanac takes several medications to prevent rejection of the hand, a similar regimen to those who have had a kidney transplant. One of the drugs, a calcineurin inhibitor called tacrolimus, has also been found to help with nerve regeneration.

Krizanac feels that he is also on the path to regaining his independence. About a month after the surgery, he was using the phone with his new hands. And while washing his hands a few months later, he was surprised when a sensation of cold water jumped off him.

“I reflexively pulled back from the cold water, and this was a really moment of thinking, ‘Oh, my god, I can feel the temperature of the water,'” he said.

Although hand-made transplants are considered an optional “quality of life” procedure, Levin says they have an obligation to provide patients like Krizanac with the same level of care and considerations as those who require a liver transplant.

“This is an area of transplantation that needs to continue to be supported. Our research, clinical care, education,” he said. “This area is hampered by the inability of insurance to pay for this or other institutions to accept it – it would really be a crime.”

Krizanac has ambitious goals that are beginning to feel more realistic, such as getting a driver’s license. He really just wants to be a normal adult.

“Everything is getting better, but this process is very complicated in terms of surgery and rehabilitation, but these are just two healthy hands and it’s just a matter of time and commitment to recover,” he said.

For now, the little things bring him great joy. He has been honing his amateur skills so he recorded his own video making espresso. Barista – A hobby that he could not have pursued without a hand transplant.

“I’m more of a cappuccino guy, but he can always make me espresso,” Levin said.